Jean Rhys is my favourite novelist, and has been ever since someone gave me an extremely bashed-up and coffee-stained copy of her novel Good Morning, Midnight when I was eighteen. A few weeks ago I picked up the collected novels and re-read one called After Leaving Mr Mackenzie for the first time in ten years.

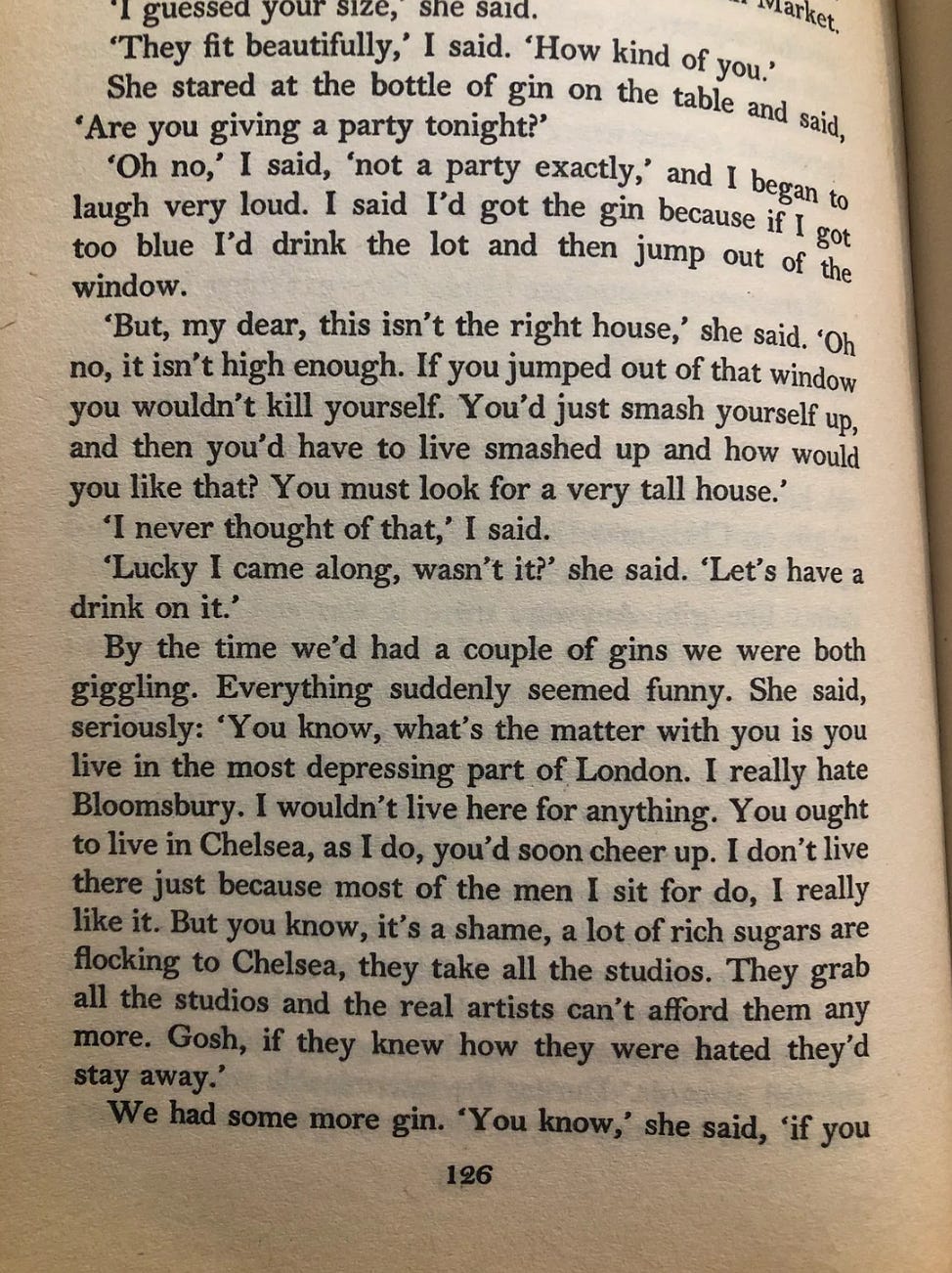

Like all Rhy novels really, it’s a book about rooms – cheap hotel rooms, bedsits, cafes, bars and chilly bedrooms in Bloomsbury boarding houses. Rhysian women occupy various rooms to hide in refuge from the world outside, and crucially all of these rooms are temporary. As the protagonist of GMM proclaims: “a room is, after all, a place where you hide from the wolves. That's all any room is.” Rooms are refuges from the world but more often than not, they are also where the world takes place. Rhys’s women drink, write, dress, bathe and have merciless, often reluctant sex in an endless series of impermanent rooms from Bloomsbury to Montparnasse to the Dominican estate of her childhood. It was in a cheap bedsit in Chelsea, recovering from what was then called “an illegal operation” that Rhys would first try writing, frantically filling three exercise books with the details of her chaotic early London years which she would later metabolise into her novel Voyage in the Dark (which the title of this post is taken from.) I’ve always had a romance about women’s boarding houses. Imagine a cheap room in central London in a house full of single women, with a landlady who lights the fire in the morning and leaves your breakfast on a tray outside the door. Almost all my favourite books were borne of this culture. The boarding houses of Rhys’s generation offered a kind of freedom to women who wanted to write or be artists that I’m not sure has ever really been afforded in the same way since. I for one would love if we re-established the tradition.

Over Christmas in London I read Rhys’s unfinished autobiography Smile Please1, the last text she was working on before she died in her late eighties. The first half takes place in the Caribbean, in Martinique and Dominica where Rhys lived as a child descended from a former slave owning grandfather, on an estate constantly being set on fire (inspiration for Wide Sargasso Sea.) The second half of the book is made up of unfinished sketches of her life after she sailed to England to attend school at sixteen, where she briefly attended an acting course at RADA before dropping out when her father died and could no longer pay the tuition. Instead Rhys became a chorus girl a toured around the UK, singing and dancing nightly on the strangest provincial stages.

When I walked around the grey Bloomsbury streets this Christmas I looked for traces of Rhys, which was not her real name, but just one of many she adopted over the years. Sometimes she was Gwen, the name she’d grown up with, and sometimes she was Ella, or Vivienne, or Emma Gray. She became Jean Rhys is 1924 under the suggestion of her mentor, publisher and sometimes-lover Ford Madox Ford, who was a much older, married and well-established writer and for better or worse is credited with first discovering her literary talents. Changing one’s name with the seasons means that traces are often hard to find. Very few letters from the early turbulent years of her adulthood survive, and apart from the three frantic exercise books she didn’t keep a diary. When I looked for a house in Torrington Square2 she boarded in around 1917 I walked around in circles before realising the square is now a university campus and no longer exists as it did when she lived there.

When I first moved to London I was newly 19, I had dropped out of university in Ireland and relocated myself on a whim because I had fallen in love, though I wouldn’t admit that to myself until several years later. I also spent many nights singing on strange provincial stages. I was mostly weird and lonely and wandered around by myself reading mid-century books and drinking cloudy Pernod because it’s what the people in those books drank even if I didn’t know how to pronounce it then. I had adopted a new name too, or a new version of a name I’d always used but that still wasn’t my official first name, which confusingly I’d never used at all. Including the man I’d fallen in love with (the one who first gave me Good Morning, Midnight), almost everyone I’d met that year was using a self-adopted name, people whose identities were intentionally vague, and who now as a result I’ve completely lost all hope of contact with. S, the man I was in love with, published poetry under one invented name, had a self on the internet under another. I didn’t realise for quite some time later how acutely paranoid he was. Every thing he did was veiled in secrecy, I don’t know who he thought was watching, but he obsessively covered his tracks. For years after I left him I thought perhaps I didn’t ever know him at all, but now I think surely that someone’s soul always persists, regardless of any slippery self-fashioning.

R was a woman I met one night in the place so aptly named Angel, she was about twenty years older than me and I thought immediately that she was the most beautiful person I had ever met. Later she told me she had had her face entirely reconstructed after she sustained near-fatal injuries in a traffic accident that had left her in a coma for weeks. When she finally woke up the first thing she saw was the name tag of the nurse tending to her, which was the same name of her favourite childhood horse. R was full of near-mythical encounters like this. She was the person I called when I accidentally moved into a crack-den on the marshes and only realised when, out in the garden, I saw hundreds of pieces of burnt foil littering the back step. Before I got close enough I just thought it was hundreds of sweet wrappers. I ran out, through the marshes which were already spooky enough as it was getting dark, and took the train to Angel where she bought me french martinis while we sat at a bar so polished I could see our reflections. Her name was given to her by a friend back when she was working as a caricature artist with a travelling circus. The night I turned twenty she showed me her paintings as we drank vodka and cranberry juice in her Hackney bedsit and she gave me a bin-bag full of beautiful “depression dresses” she had bought to distract herself from being unhappy. I remember taking one out on the walk to the bus stop that night, white baby-doll, antique lace, when I held it up to look at it closer it moved in the wind like a flag.

P was a man I met in a basement bar where I was singing one night, I was feeling strange because the bar was across the street from the road where a teenage friend I had died horribly when I was sixteen. P bought me a whiskey and told me that something about me was a little terrifying. I found him strange too but I liked him straight away even though I thought his keenness for me was a little unnerving. I liked his accent and we liked a lot of the same songs and we cared about poetry to similarly embarrassing degrees. He was always changing what age he was, and his name changed at least three times in the course of our strange friendship. He’d email songs he’d written for me and send me books and letters in the post. Once we met on the heath and it was only when he put down a picnic blanket and a bottle of wine and an acoustic guitar that I realised his intentions towards me were possibly beyond friendship. I was flustered and awkward and decided to run. I ran across the Heath in the dusk all the way to the overground station feeling embarrassed in the way I always did back then when I’d so blatantly misread social cues and intimate gestures. I took the train to the house of another unfortunately older man I’d befriended that summer who probably told me his real name but definitely lied about everything else. I slept in his bed when he was away at a festivals, enjoying having a big house in London full of instruments and books all to myself. One morning I reached under the bed when I woke up and picked up a slim orange-spined 1960s edition of Jean Rhys stories. You should never sleep with a man because of his taste in books, obviously, but I didn’t really know that then, and worse still, it wasn’t until much later that I realised the book had actually belonged to his wife.

Yes I did once write a song of this name. But it wasn’t my first Rhys song.

“What’s going to become of you, Miss Petronella Gray, living in a bed-sitting room in Torrington Square, with no money, no background and no nous?” (Jean Rhys, Till September Petronella)